“For me to immigrate to the United States was to take stock of what I had to give up to get what I want out of what Mary Oliver calls ‘this one wild and precious life,’” English teacher Kristine Palmero told students this week. “It’s about choosing where my physical body will be even if there are rooms in my heart that live in a house in a country so distant that their night is my day.

“For me to immigrate to the United States was to take stock of what I had to give up to get what I want out of what Mary Oliver calls ‘this one wild and precious life,’” English teacher Kristine Palmero told students this week. “It’s about choosing where my physical body will be even if there are rooms in my heart that live in a house in a country so distant that their night is my day.

“But over time, the U.S., which I thought would be no more than an interlude, turned into my home,” Palmero added. “For me, trying to immigrate here is about loving the U.S. and my life here with my whole being, even when I wasn’t sure how long I would get to stay.”

Palmero was born in the Philippines and raised in Saudi Arabia, where her father worked for an energy company—she saw how Americans working for the company received privileges other foreigners did not. Inspired by the film Dead Poets Society, she asked her parents to send her to boarding school in the United States; her father responded by gathering as much information on American prep schools as he could to help her achieve her dream.

“As many of you know, I lost my father last year,” Palmero said during a virtual program on immigration stories hosted by Milton’s Amnesty International Club. “And before writing this, I thought I was going to school you on the challenges of navigating a broken immigration system.”

She continued, “For a long time, I have been steeled by my anger as I recalled my challenges in securing a work visa and my green card, and how countries like the United States have conflated issues like national security and the economy with immigration. But draft after draft, I kept returning to a David Foster Wallace quote: ‘Every love story is a ghost story,’ and my immigration experience is just that—a love story and a ghost story.”

“For me to immigrate to the United States was to take stock of what I had to give up to get what I want out of what Mary Oliver calls ‘this one wild and precious life.’ It’s about choosing where my physical body will be even if there are rooms in my heart that live in a house in a country so distant that their night is my day. But over time, the U.S., which I thought would be no more than an interlude, turned into my home. For me, trying to immigrate here is about loving the U.S. and my life here with my whole being, even when I wasn’t sure how long I would get to stay.”

– Kristine Palmero, English Department faculty member

The program was hosted by students Doan Tran ’22 and Dylan Arevian ’22, as well as Mai Le ’24, who has been working with Project Citizenship, a nonprofit that provides free legal services for immigrants in Massachusetts. Melissa Lawlor, the Upper School Director of Equity, introduced the event with her own story of her lengthy process to receive U.S. citizenship.

Dr. Mitra Shavarini, the executive director of Project Citizenship, joined the event with a prerecorded message about the organization and its mission.

Citizenship or naturalization is “that last, final gate for immigrants to live in this country, to belong to this country,” Shavarini said. “It’s at the end of a very long road, literally and figuratively.” Seventy-three percent of the people the organization helped last year were front-line workers who have provided essential services during the COVID-19 pandemic, she said. Citizenship in the United States confers many rights and federal benefits and provides citizens with one of the most powerful passports in the world.

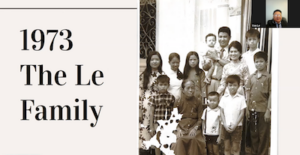

Both Palmero and speaker Van Paul Le—Mai’s father, who as a boy came to the U.S. with his family, refugees escaping Vietnam during the war—described the kindness and generosity with which they were supported by friends and mentors during the long, costly, and frustrating immigration process.

Van Le, now an attorney in Boston, moved around the U.S. as his father—who had been a successful and respected business developer in Vietnam—searched for work. He shared stories about his harrowing early days before his family escaped, including an attempt by the Viet Cong to assassinate his father, during which both Van and his mother were injured by gunshots. They were treated by an American military doctor, John Lloyd, and the families became friends. The Lloyds ultimately sponsored the Le family in the U.S. after they escaped, first on an overcrowded tugboat, and then on a U.S. Navy ship. Le’s mother died before the family could leave.

“Where we once gave donations in Vietnam, now we were receiving them,” Le said. “My father’s first job in America was to work as a janitor…. He had lost everything: his business, his wealth, his status, his country, and his wife.” Le and his siblings entered their American school without knowing much English, but gradually learned; his dad was adamant that the children would go to college.

“Where we once gave donations in Vietnam, now we were receiving them,” Le said. “My father’s first job in America was to work as a janitor…. He had lost everything: his business, his wealth, his status, his country, and his wife.” Le and his siblings entered their American school without knowing much English, but gradually learned; his dad was adamant that the children would go to college.

Eventually, Le was sent to Boston to live with his grandmother and his siblings while his father moved around for work. He received good grades and admission to a private high school, where he encountered “lots of Robert Frost and theoretical math.” As a young adult, he taught English to Vietnamese refugees living in camps to prepare them to apply for resettlement abroad. He is grateful for the support and sacrifices his family made in spite of the many challenges they faced.

“Looking back, I know I was one of the lucky ones,” Le said. “Many of the refugees from the Vietnam War didn’t make it. It’s estimated that roughly half of the people (who attempted to escape) died at sea.

“I don’t believe my story is unique, it is the story of many other Vietnamese ‘boat people,’ some facing much more trauma and difficulties,” he continued. “I do believe that, like so many newcomers to America, refugees and immigrants bring lots of hope, truly believing in the American dream and opportunity. Freedom becomes a very real, cherished thing once you have lost it.”